Avoid Getting Dressed in the Dark: Problem Solving For Law Students

I offended some of my students in Public International Law this past week. Following a heated discussion on the anachronistic character of executive prerogatives in modern treaty making, I declared that my students possessed rubbish problem solving skills. Tact has never been my strong suit.

While the criticism was unnecessary, the point is critical. Many (most) of my law students are not well versed in problem solving strategies. To be crude, they approach legal problems in much the same way as they tackle birthday gifts: making educated guesses in the hopes of satisfying the honouree. In an academic setting, their aim is to satisfy the lecturer.

Students are hardly to blame for their flawed approach. Most modern law schools have not prioritised the development of problem solving skills, only demanding this in the context of exams / essays and without the necessary training and practice. As a result of this shortcoming in their education, many students fail to learn the fundamentals of legal argumentation, ultimately inhibiting their potential both within and beyond law school. What can be done about this?

***

In a previous post, I argued that linguistic intelligence is vital to the study of law. A key element of linguistic intelligence is the ability to develop and deploy persuasive arguments. Persuasiveness, however, is an altogether different standard to accuracy. Let me explain. To carry out a mathematical equation, we require the correct variable and process: multiplying 5 by 20 is different from dividing 105 by 15. Without the correct variables and processes, it is impossible to solve a mathematical problem hence why mathematicians strive for accuracy. Not so for jurists.

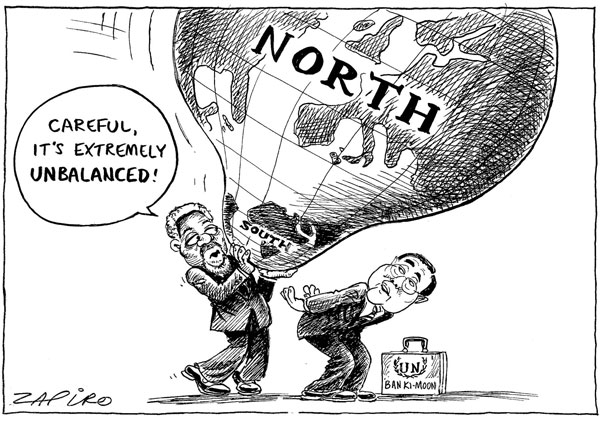

In contrast to what many law students believe, laws are indeterminate: the outcome in a legal dispute depends as much on the oratory skill of the advocate as it does on the identification / application of the relevant law to the relevant facts. Consider, for example, that the Supreme Court regularly reaches majority decisions: judges applying the same law to the same facts reach opposing conclusions. Are the minority judges simply wrong? That seems a silly conclusion. The advocates of one party made more persuasive arguments than the advocates of the other. If the standard in operation were one of accuracy, judges would reach unanimous decisions at every go. Instead, since laws are indeterminate, the standard that operates in legal circles differs from that of mathematicians. In our discipline, persuasiveness rules the roost.

In line with last week’s criticism, problem-solving strategies are ideal tools in the development of persuasive arguments. Since no single answer is conclusive, we approach legal disputes – whether in the context of an essay, an exam question, or a thesis – with an eye to building convincing arguments. My word choices are deliberate: we develop, craft, and shape ‘convincing’ arguments. By this I mean that, instead of thinking like a detective, rummaging around in search of the truth, see yourself as an architect, someone who designs arguments and an engineer, someone who builds them with sturdy and lasting materials.

***

Sturdiness is best achieved through a systematic approach. In general, I teach law students the RIREAC form: Reference – Issue – Rule – Explanation – Application – Conclusion. There are others (IRAC / ILAC are more popular) and I have met people who prefer to adopt bespoke forms (HOPP: Hunch – Optimistic View – Pessimistic View – Provocative View). Regardless as to which form(s) you opt for, practice is critical and I encourage you to experiment with a variety of strategies though will focus this post on the RIREAC form only.

Each element in the RIREAC form is selected and ordered to create a ‘logic funnel’: what is poured down the top comes out of the bottom just in a more compressed and coherent format. Using Lotus, a primordial decision of the (Permanent) International Court of Justice, let us work through an example.

The backstory is simple. A Turkish and a French ship collide in the high seas killing multiple Turkish sailors in the process. Due to the negligence that precipitated the accident, the Turkish government launches criminal proceedings against both ship captains for the deaths. The French government protests: the captain of the French ship is a foreign national operating in international waters and thus not under Turkish jurisdiction. Both nations agree to refer the matter to the ICJ.

I- Reference

How should the ICJ deal with the matter? Most law students would advise applying the law to the issue at hand. But it is not this simple since the relevant law depends on the point of reference selected by the court. Should the court tackle the dispute from a jurisdictional angle (public law) or perhaps a liability one (maritime law)? It could decide to account for the laws of both jurisdictions (conflicts of law) or it could tackle its own jurisdiction over the affair (by reference to the ICJ’s constitutive statute).

In short, instructing judges to apply the law does not get us very far. An initial choice must be made about the reference before a law can be identified. Of course the decision is subjective and jurists will frame the problem differently, resulting in much frustration and squandered time. In most instances, there is no natural referent and jurists opt to frame the problem in a manner that plays to their client’s strengths or, more often than not, to their personal capacities. Of course, when constituting what the problem is, we also constitute what the problem is not (meaning we exclude possibilities in the process). Awareness of what is framed in and what is framed out is essential in understanding the intricacies of the matter at hand. For example, the ICJ avoided all of the referents I mentioned above, opting instead to examine the dispute through a theoretical lens: what is the nature of international law and what does this mean for the matter under examination? I will explain their approach in more detail in the forthcoming section.

What is important for the budding jurist (or current law student) to note is that their choice is more straightforward than the decision of a court: you need simply identify the referent that you will apply to the problem. For the clever law student, this translates into greater autonomy over their learning. By deciding the reference / frame, they decide which aspect of the topic they will investigate and thus which they will learn about. Framing is an empowering exercise and one that students at all levels of their education should embrace.

II- Issue

Issue spotting is better described as second-order framing. To engage the matter further, we must identify the issues that are suitable for investigation. Some questions make sense legally – can we design adoption laws to enhance efficiency in the placement of foster children? – while others make sense sociologically – why is the number of foster children in the UK rising? Framing the issue can make a jurist’s life easier or, as per the second question, impossible. To the extent that there is a rule of thumb, it is to frame the issue in a manner that can be resolved by drawing upon laws and legal argumentation. A rising number of foster children may have something to do with law – draconian placement standards for example – but is more likely the product of political economy factors.

Returning to Lotus, how did the ICJ pursue the matter? Recall that the court’s referent was the nature of international law. Following the funnel formal, the issue must flow from the reference and so it is of little surprise when we learn that the court asked the following question: ‘does international law prohibit a nation-state from bringing criminal charges against a foreign national for activities in international waters’? Of course they could have framed the question differently: ‘does international law permit a nation-state from bringing criminal charges against…’? And, as per the reference, it is always useful to reflect on what is framed out as much as what is framed in. The court presented the issue in the former manner to conceptualise international law as a permissive system – where all behaviour is permitted unless expressly prohibited – as opposed to the latter manner which would have limited international law to behaviours that have been specifically permitted (a prohibitive system). In short, similar to the reference choice, issue spotting is also a subjective exercise that opens some doors while deliberately closing others.

III- Rule

Law students will be happy to learn that the heavy lifting is mostly over. With reference and issue framed, we now move to the analysis portion of the exercise. It is at this stage that we identify the relevant rule. Having already fenced our examination within narrow parameters, rule identification is clear-cut. For example, once we frame a matter within criminal law and decide that the issue pertains to standards of care required of parents toward children, we know precisely which statute(s) to look to. Indeed, with reference and issue at hand, we are left with few options as to the relevant rules.

My own approach involves a multi-layered assessment. 1) I begin by asking myself about the relevant jurisdiction: transnational, international, municipal, or local. 2) Next I determine if primary or secondary legislation is likely of relevance. For example, if the matter pertains to the liability of a solicitor for negligent legal representation, the Solicitors Regulation Act, a piece of secondary legislation, is my first port of call. 3) With rule in hand, I pinpoint a judgement that relies on the relevant provision and, voila, acquire a near complete list of the relevant rules as well as a useful example of the application of the rules to a germane dispute.

IV- Explanation

To apply the rule successfully, a student must understand the rule sufficiently and there is no better way of achieving understanding than by explaining the rule. To be sure, an explanation is not a recitation and it would be a mistake to merely restate the provision (which students are known to do). Explaining the rule is a rigorous exercise that is best tackled systematically.

I prefer to apply a sociolegal lens when explaining a rule. In the initial stage, this involves analysing the rule itself. Which terms were included / excluded? Does the statement create a positive obligation or does it provide standards against which behaviour will be measured? Engagement with the text is essential. In the second stage, I seek to uncover the ambition of the law. What did the legislature intend? What concerns was the legislature looking to address? Parliamentary debates (Hansard) are useful in this regard as are press statements made by the proposing / opposing parties. Here we uncover the subtext. In the third stage, the circumstances surrounding the adoption of the law are most relevant. When was the law adopted? Did it follow a trend or does it break from tradition? The context within which the rule was adopted provides greater nuance to the rule.

By investigating the text, subtext, and context of a rule, you are more apt to explain the rule and thus more capable of applying it convincingly.

V- Application

Despite being the simplest part of the exercise, students often stumble on the application. My sense is that doubt creeps in at the later stages causing their confidence in the preceding steps to fray. Rest assured that if the R-I-R-E stages are conducted systematically, the application is as smooth as Andre 3000 in silk pyjamas.

What matters most in the application stage is the identification of relevant facts. Recall that the problem is twice framed: reference and issue. Following this, the rule is identified and explained. Determining which facts matter is thus contingent on the fences already erected. Out of fear of missing something, students usually adopt the kitchen sink approach, carpet-bombing the reader with every fact identified in the scenario, ultimately shoehorning bunkum into an otherwise logical analysis. In the process, they undermine their own credibility by intimating a misunderstanding of the very fences they have built. It is akin to sautéing vegetables with basil, rosemary, thyme, paprika, and parsley (herbs) followed by a mix of curry, cayenne, and chipotle and finishing with tamari, Dijon, and ketchup (sauces). Just because these condiments are available does not mean that they should be used. Instead, we select the ones that will complement the taste of our concoction or, in legal terms, we select the facts that will contribute to the persuasiveness of the argument we are developing.

V- Conclusion

Personally, I regard conclusions as works of art. Of course they can be delivered in a pro forma manner, restating what was said and summarising the main points. Law school and legal practice, however, are not judged according to secondary school standards and replicating a model that served you well in your A-levels is a sure fire way of torpedoing an otherwise rigorous argument. Recall that, in law, our aim is to persuade. The conclusion is thus opportunity to leave your reader with a sense of confidence in the argument you have made. Restating what was said is redundant and, worse, banal, failing to make your argument memorable.

The conclusion is thus your opportunity to demonstrate a little – preferably a lot – of rhetorical force and flair. Conclude confidently, nimbly, and, most of all, convincingly.

***

Adopting systematic approaches toward legal problem solving and legal analysis, approaches that favour persuasive over accurate arguments, ensures that you develop robust thinking and rhetorical skills. These skills will serve you well both during and beyond your legal education. More importantly, however, they will also ensure that you ‘never get dressed in the dark.’

2 Comments

QUB Student

It will be best if you can provide us with an example argument using RIREAC Approach so that we can understand more deeply how a good argument can be drawn.

Mohsen al Attar

Good idea. I’ll upload an example next week.