Just Follow the Money: The Misery of International Law

I draw your attention to the title. It is an amalgamation of two phrases. Just follow the moneyis pithy, even a little crass. It is often uttered in television crime dramas, usually to aid the protagonist identify the culprit. The Misery of International Lawis the title of a book by Linarelli, Salomon, and Sornorajah. So provocative is this text on International Economic Law (IEL) that it is subject to at least four review essays: see Kanad Bagchi, Juliea Dehm, Nicholas Perrone, and me. In their book, the trio argue that IEL supports the immiseration of an array of classes and societies. They provide extensive evidence that the regime has done so since its inception, concluding that we have every reason to suspect that it always will.

Each phrase in the title of my talk encapsulates a device that, I argue in this essay, is essential to the study of international law (and not just IEL). Without these devices, the system appears capricious, if not flawed. Many students, just like many academics, must resort to varying degrees of cognitive dissonance to square the circle. For example, all states are equal but permanent members of the Security Council are more equal than others; all states enjoy absolute sovereignty unless Euro-American states decide they do not approve of the ruling authority and wish to overthrow it (until they don’t); and to become a nation-state, a people need only declare themselves so unless other states dismiss their declaration. Publicists will instantly recognise these conundrums and recall the discomfort we feel when students ask us, in all earnestness, to explain the contradictions.

My own solution when confronted by international law’s paradoxes is what I present today. To make sense of the contradictions of international law, we need to do two things: just follow the money and acknowledge that international law’s Janus-faced character will produce much misery for the world. That is the thesis of this essay.

I proceed in two parts. In the first, I set out four premises that inform my thinking about international law. Without these, you will not understand the second half, in which I explain the influence money and misery wield over the system.

1- International economic law is an instrument of social engineering

My first premise begins with the widespread misunderstanding of international economic law. If enrolment numbers are indicative, the subject is less popular during the study of law than other international legal subfields. I generalise but there is mounting evidence that students prefer international criminal, commercial, environmental, and possibly even humanitarian law. The word ‘economic’ is the source of student angst. Will the course involve macro or micro economics, whatever those happen to be? Must I be proficient in mathematics? Will I still perform well even if I don’t understand the global economy? Law students are not unique in their fear for economic illiteracy is pervasive.

To say that international economic law regulates economic relations between states is, of course, accurate. Most professors dedicate the bulk of their syllabi to the regulation of trade, investment, and money. More so than economics, a grounding in political economy would serve students well. Yet, what is left out is most important of all: IEL is also a field of social engineering. The international financial institutions, custodians of the framework, offer answers to two core questions: how should we regulate economic relations and who should regulate them? The first question is normative and the second is political, meaning we cannot answer either objectively. In fact, the subjectivity of the answers is the source of much consternation, controversy, and incoherence within IEL. I explain this point with an obvious example.

IEL developed in the post-war period to account for increasing economic interdependence. The denationalisation of production and finance (globalisation) solicited the demand for inter-state cooperation. An absolute conception of sovereignty, one that presupposes 18th century forms of autonomy, was anachronistic. States had to cooperate, as they did when establishing the IFIs. Still, then like now, our outlook remains wedded to a nationalist, mercantile, and often nativist standpoint. Here, we ask not how can we cooperate, but how I maximise my self-interest.

In a world of scarce resources and a nation-state form of organisation, the answer is blunt: at the expense of others. An us or them outlook is antithetical to the cooperative drive that allegedly guides international law, yet both coexist generating the incoherences that plague its operations. Engagement with the normative and political questions is necessary to reconcile the contradiction.

2- International law does not value cooperation

Another misunderstanding informs my second premise: IEL is the regulatory regime for global capitalism. Like IEL, capitalism also has two facets. As an economic system, it compels endless accumulation. By growing their wealth, even to cartoon proportions, capitalists like Bezos, Mittal, Gates, and Ma are doing exactly as the logic of capital commands. As a political system, it posits that the market is the most efficient mechanism for the distribution of scarce resources. Even the economically illiterate are familiar with this axiom. Yet the political implications of the market are glossed over, not to say concealed outright.

Champions of capitalism proclaim that the market is a democratic framework. Why? Because market actors chooseif and how they wish to participate. This claim, however, is deceptive. If the market is the only mechanism for the acquisition of scarce and essential goods – think privatisation of water or food – then participation is not voluntary: neither hunger nor thirst are genuine alternatives. Beyond its coercive character, we must also acknowledge that market actors are not equal and those with greater wealth enjoy more influence over a market’s operations. We call governance by wealth a plutocracy, a term unfamiliar to most despite its relevance to a market system.

Plutocracies are egotistical systems that provoke predatory behaviour. Again, market actors maximise self-interest at the expense of others. Even the denial of essential goods to others is valid if it strengthens an actor’s position within the marketplace. It is an adversarial system at its core that yields endless conflict.

If IEL is the regulatory regime for global capitalism, if capitalism is egotistical and predatory, then how is the legal regime to facilitate cooperation? Economic actors value their interdependence only to the extent that it improves their standing, at which point their predatory instincts take over. Cooperation within a capitalist social system is a fallacy.

3- International law universalises European interests

International law evolved from the encounter between Europeans and peoples beyond Europe. Thanks to Antony Anghie and others, the history is well known and need not repeating here. It is sufficient to recognise that Colon’s voyages were motivated by mammon. His aspirations, along with those of Ferdinand, Isabella, and other imperialist monarchs, established the foundations of European international law, gradually universalised as a global system.

Recall the rights and responsibilities that emerged within Vitoria’s natural system of jus gentiumor law of peoples: to trade, to settle, and to proselytise. Notice the centrality of economic interests to Vitoria’s thinking. Access to markets and resources were primordial in the framework, as was European morality which the natives were legally bound to accept. Conquest was symbiotic to the development of international law and vice-versa. Natives were coerced into trading relationships and expropriated from their lands. In fact, the use of force was common when seeking to extend European economic interests, always under the cover of an emergent legality (for those who wish to read more on this, I recommend James Gathii’s War, Commerce, and International Law, Sven Beckert’s Empire of Cotton, and Michael Fakhri’s Sugar and the Making of International Trade Law).

Despite repeated attempts to reform our thinking about Eurocentrism in international law or to rehabilitate the framework of its incestuous relationship with conquest, it remains prejudiced and prejudicial, both aetiologically and epistemologically.

4- International law is violence

To study international law is to study violence and its legalisation. That violence is widely excluded from legal textbooks is down to Eurocentrism and continued European denial of the barbarism of European behaviour, both historically and contemporaneously.

A facile example is the famed Century of Peace or Pax Britannica. Coinciding with the first period of globalisation, this period stands out in European history for the curtailment of Catholic-Protestant warring. Europeans achieved a compromise that lasted until the first Great European War of the 20th century. Most telling is not the supposed peaceful relations but the self-centredness of the narrative.

Consider that the century of peace occurred just as Europe was rampaging across other continents, visiting war and savagery upon the rest of the world. During this same period, they orchestrated colonisation and famines in South Asia; colonisation, enslavement, and genocide in Africa; blockades, counter-revolutions, and exploitation in the Caribbean and the Americas at large. Vitoria, Grotius, and Vattel each crafted European international law to legitimise the varying rounds of violence visited upon the rest of the world.

It bears mentioning that, despite its depravity, these were not episodes of naked violence but purposeful. Following the edicts of jus gentium, they did so to gain access to the markets and resources of others, as the logic of capital compels.

With these premises in hand, we move to the second half of this essay, where I explain why money and misery are essential devices in the study of international law.

***

First, while the early days of international law were informed by the desire of European monarchs to plunder others, its later stages were shaped principally by capitalism. As highlighted above, capitalism centres the private accumulation of wealth. It also centres the market in the allocation of scarce resources. Both characteristics manifest within international law producing what Sornarajah terms a market-based international law.

In Plunder, Mattei and Nader argue that despite the pomp that surrounds the Rule of Law, it exists primarily to formalise two rights: property and contract. Rule of Law projects promoted by the American Bar Association, the European Commission, and the IFIs begin and end with private proprietary rights on one end and the freedom to contract on the other. Both are intertwined within a liberal conception of liberty that amplifies individual desire and choice in social organisation: we must be permitted to acquire what we want so long as we can afford it.

The intimate relationship between property and international law dates back to the days of Vitoria. During the colonial period, it was common for settler-colonialists to register and parcel indigenous lands. Titles were thereafter distributed to members of local tribes before being bought back by the same colonisers, a clever mechanism for acquiring legal title over the lands of others and extinguishing any future claims by Indigenous peoples. This practice was systematically deployed across settler-colonial states, even those widely regarded as progressive such as Canada and New Zealand.

Borrowing from this perverse practice, the IFIs demand that Third World states establish a Rule of Law compliant framework before they will permit any loans. Fuzzy norms such as democracy, equality, and welfare are not determinative in their representation of the Rule of Law. Rather, they must commit to a regime of private property rights.

So central is this standpoint that states often demand the dismantling of any systems that might conflict with private ownership. State-owned-enterprises are the obvious one, yet collective forms of land tenure also fall afoul. Included in the North American Free Trade Agreement, for example, was a commitment of the Mexican state to limit the use of the ejido, a system of peasant land ownership.

The universalisation of a system of private accumulation of wealth was made possible through the project of capitalism and the project of international law. To teach international law thus demands in-depth engagement with political economy or, in simpler terms, with money.

Second, due to the dispossession that is intrinsic to capitalist modes of production, compliance with IEL invariably leads to reconfigurations in distribution of all goods including essential ones. The examples are too numerous to mention though I highlight the studies on financial crises including, for illustrative purposes, the economic slowdown precipitated by COVID-19. With every financial crisis, we note that the wealthy make a killing. In 2020 alone, the world’s billionaires increased their aggregate wealth by 27.5%.

Following the prescriptions of the IFIs produces higher levels of relative poverty while concurrently reducing programmes of social welfare. Naomi Klein’s Shock Doctrine, perhaps because of its journalistic character, provides ample evidence of the ways in which crises are turned to the advantage of the affluent. Treat with suspicion anyone who utters the phrase we’re all in this together. As the vaccination wars verify, we never are.

Perhaps Susan Marks has gone furthest in developing exploitation as an analytic concept in legal scholarship. In one elucidative piece, she argues that exploitation is good business. Instead of treating poverty or wealth as condition, we should conceptualise them as relationships and historical processes. In a world of scarce resources, accumulation by some translates to dispossession for others. For my own part, when teaching IEL, I speak not of poverty but of the politics, economics, and legality of impoverishment and immiseration, and the role of international law in both exacerbating and redressing them.

Linarelli, Salomon, and Sornorajah develop this point in their own unique way. They speak of international law’s trade in sleight of hand, where distractions are deployed to disguise the misery it instigates. For example, international law is built on fabricated categories. Notice, for example, the fallacious separation of the economic and non-economic realms. Scholars compose entire textbooks on international law that exclude references to the economic, just as their colleagues in IEL produce their own textbooks that make nary a mention justice or poverty, let alone injustice and impoverishment.

In this way, an inside-outside distinction, perhaps dichotomy emerges. We learn that issues of justice, distribution, access to essential goods are situated inside the state. By contrast, economics are best regulated by IFIs and, preferably, a cadre of private dispute resolution experts – mediators and arbitrators – all of whom operate beyond the state. Its a clever tactic. To participate in the global economy, states must surrender authority over their economies to the diktats of IFIs. For their part, IFIs must refrain from commenting on the political or moral preferences of nation-states, lest we accuse them of trespassing over national sovereignty. The end result is that what happens outside the state is not subject to any moral demands beyond the sanctity of property, contract, and debt.

Neither misery nor poverty are analytical categories in international law. For that matter, neither is money. Yet, international law is shaped by an economic project which, at its core, legalises the private accumulation of wealth. In a world of scarce resources, in a world beset with inequalities, accumulation is not benign. As some accumulate more, less is available to everyone else, producing much misery for those who are incapable of leveraging market power to their advantage. That is the nature of capitalism and, by extension, the nature of international law.

To understand international law demands engagement with the underlying political economy. When assessing treaties or rulings, when examining proposals for reform, I always ask myself two questions: where’s the money and who will this immiserate? Be forewarned: your perception of international law will never recover.

***

The preceding are reflections on a talk I delivered at UNAM, as part of their annual Critica Juridica conference. You can watch my presentation as well as that of the other panelists here (my talk begins at minute 40 or so).

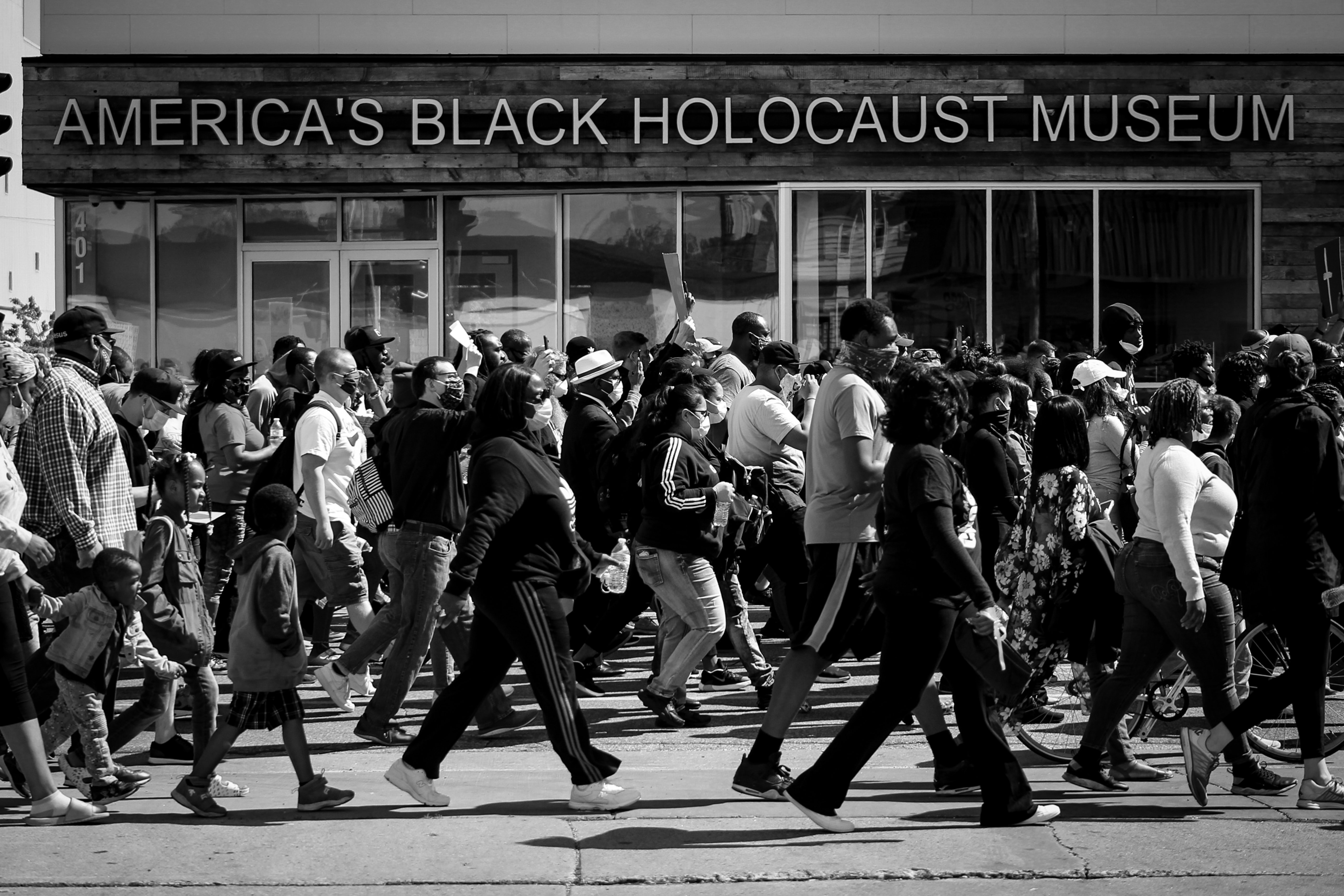

Photo by Zeyn Afuang on Unsplash.