When Human Rights Violations Go Unnoticed

Who is the greatest violator of human rights? I often gauge student awareness about global politics with this question. Responses vary according to the political persuasion of the respondent: some students focus on states – the USA, Israel, Russia, China, Saudi Arabia, and Zimbabwe are go-to countries – while others name individuals – Tony Blair, Vladimir Putin, Saddam Hussein, Benjamin Netanyahu, Osama Bin Laden, and other notorieties make regular appearances. In five years of posing this question to (law) students, not one has gotten it right though the lack of success has more to do with representations of human rights than with the intellectual shortcomings of (law) students. The answer is poverty.

Strange as it may seem, poverty is the greatest human rights culprit, striking with a level of ruthlessness that Donald Trump can only fantasise about. Poverty is a crucial source of illness, homelessness, violence, addiction, incarceration, hopelessness, and, of course, death. Consider that in the time it has taken you to read these paragraphs, hundreds of people have died of hunger related causes. This figure is even more damning when we factor in the many tonnes of food Brits have binned in the past few minutes alone.

Despite being a blatant plague on human existence, poverty is almost never identified, by students or otherwise, as a nemesis of human dignity. Why not? We are taught to view poverty as a condition: a misfortune that befalls the wretched or an inevitability of idleness. Conceptualised in this manner, poverty is either the fault of fate or the fault of the poor absolving society of any collective responsibility. In the process, human rights are made irrelevant to the poverty debate. But are they?

***

In its early years, human rights were designed to counter state impunity; to protect individuals against the state’s monopoly over violence. Following the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human rights, states and their agents would henceforth be held to account for breaching minimal standards of treatment. State duty was conceptualised as negative – the state must refrain from interfering with the enjoyment of a freedom – or positive – the state must enable the enjoyment of a right. Early human rights focused heavily on the interactions between states and individuals.

Human rights evolved during their adolescence. We came to realise that constraining state behaviour reduces some violations of human dignity but does not redress human suffering, prompting efforts toward the adoption of a thicker conception of human rights, one that actively uplifts human dignity rather than merely protecting it. Through social policy, states would intervene to make life more liveable: healthcare, education, fair wages, and more were codified, sometimes constitutionalised, in a plethora of domestic and international human rights treaties.

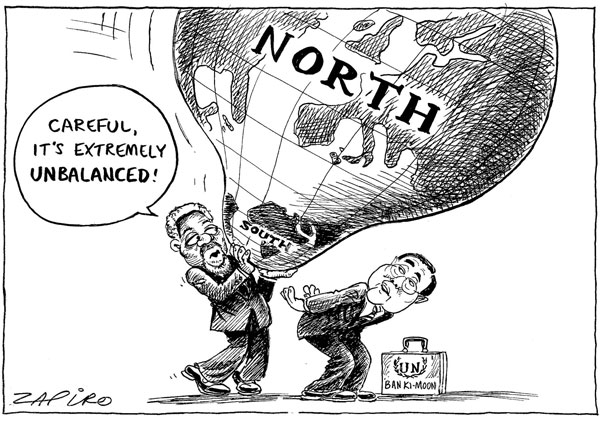

No longer would we treat poverty as the misfortune of the many. Instead, we would conceptualise it relationally and look to inequalities in distribution and the active impoverishment of peoples. A relational approach to poverty recognises that, in a world of finite resources, for some to have more others must invariably have less and, similarly, for a few to be obscenely rich, a majority must live in abject poverty. As I explained previously, universal social policy was the mechanism through which wealth would be redistributed with greater equity, mobilising collectives to counter the cruelty not of poverty but of impoverishment. In this period, human rights achieved a communal character. To be sure, they were still mediated by the state, but it had more to do with solidarity within and between societies than adversariality between citizens and states.

Social policy as pathway to redistribution worked well in many European societies, raising living standards and enhancing human dignity, at least until economic globalisation wrecked the budding consensus.

***

We are now squarely in human rights’ adulthood and observe the de-evolution of dignity. Instead of building on the successes, we shifted into reverse, abandoning rising living standards as a benchmark of human dignity, thus freeing individuals from any commitment to the collective. The retreat has much to do with the nature of human rights itself and the fetishisation of individual liberty. In a variety of settings, over-emphasis of the individual is used to dismantle collective initiatives. In Canada, the individual right to liberty was used to erode safeguards for universal healthcare; in Egypt, the individual right to property was used to counter limits on land ownership; and in many different nations, an individual representation of freedom of association was used to break up unions. In all instances, collective preferences and safeguards are made subordinate to individual choice. We have here the final paradox.

Human rights exist to protect / promote human dignity. Yet, human dignity is a layered concept that draws both from our culture and from our personality: we are products of our environment, yes, but the collective outlook we acquire is fused with our personalities producing the basis of human dignity. Like snowflakes, humans are unique and possess preferences about what matters and what does not. Also like snowflakes, however, humans are also snow, blending with other snowflakes to stimulate our sense of social belonging and thus to our experience of human dignity. If human rights are to achieve their aim, a balance must always be struck between individual and collective interest. Many of the latest rulings pertaining to human rights, such as the ones mentioned above, fail to acknowledge the inevitable balance, leveraging individual liberty in service of the dismantling of safeguards to collective welfare.

In our current conception of human rights, the individual is regarded as exceptional, supreme even, and thus matters above everything else. In this way, human rights have been hijacked and redirected toward the protection of personal prejudice and personal wealth, with both posing as human dignity. Within this conception of rights, subsidised healthcare, housing, and education can be presented – and undone – as human rights violations. Taken to its logical conclusion, individual freedom comes to include freedom from all forms of collective constraints including taxation, the lifeblood of collective welfare. In the latest iteration of human rights, the individual and the community are pitted against one another with the state ascribed the duty of the individual personal bodyguard.

Following this line of reasoning, poverty is again made irrelevant to human rights as we shift away from a relational conception – impoverishment – and back to a circumstantial one – fate / fault. Hence the paradox: individual liberty has become a ballast against instruments of generalised human welfare undermining our human dignity in the process. And round and round the human rights paradoxes go.