Of Palestinian Liars and Israeli Saints: Confronting Anti-Palestinian Racism in International Law

“I can’t stand [Netanyahu]. He’s a liar.”

“You’re tired of him; what about me? I have to deal with him every day.”

Sarkozy and Obama in conversation about the Israeli prime minister

Justice hinges on the voices heard, whether in courts or across media platforms. It also depends on the credibility afforded to these same speakers. In legal systems, we presume truthfulness, believing that reciprocal trust fosters efficiency—endless scepticism would paralyse the law—and fairness: guarding against the entrenchment of lazy hierarchies. Ideally, a person’s status, citizen or visa-holder, wealthy or struggling, will not influence the credence we afford them. To do otherwise would undermine the equality principle upon which legal systems are fashioned. Reality, however, often belies this ideal, revealing a world where prejudice colours perception, where testimonies are overshadowed by societal biases.

This disparity is nowhere more evident than in the western treatment of Palestinian and Israeli narratives. Stereotypes and prejudices skew discourse surrounding the Palestinian struggle against Israeli occupation, drawing a sharp line between those we believe and those we dismiss (not to mention those we hear at all). While the long shadow of inequality is not new to the Levant, the events of the past six months have catapulted these issues to the fore, ironically, leaving the credibility of international law and its interlocutors in tatters.

These opening remarks set the stage for a brief exploration of epistemic injustice. In tackling this topic, my aim is to provoke reflection on the systemic biases that betray the principles upon which international law purports to stand and which lead to the litany of monstrosities we are witnessing today. By probing testimonial injustice as it plays out amongst Palestinians and Israelis, we will confront uncomfortable truths. My aim with this confrontation is two-fold: first, to explain the relationship between testimonial (in)justice and legal discourse and, second, to spark reflection on how anti-Palestinian racism is exacerbating epistemic injustice in international law.

Of Credibility Deficits and Credibility Excesses

Credibility is funny business. In our everyday interactions, the credibility we afford to a speaker rests not just on the content of their speech: we also make surface-level judgements based upon subjective attributions. Does the speaker appear confident or insecure? Are they assertive or do they hesitate? Is their shirt pressed or does it look frumpy? These superficialities play to the speaker’s ethos, and influence the weight we afford their words. Knowledge and skill are also relevant, to be sure, and our assessment of these qualities should be viewed as complementary rather than separate from its superficial counterpart. Of course, knowledge and skill are also funny business with our appreciation of ability depending on substance and prejudice as well.

In academia, the politics of attribution are captured in the concept of testimonial justice. A decade ago, Miranda Fricker initiated a debate about testimonial injustice, arguing that “attributions of insincerity, irrationality, and incompetence” had less to do with the speaker’s capacities than they did with “identity prejudice in the hearer.” In other words, stereotypes precondition us to see speakers from certain social groups as less credible, entrenching a cycle of discrimination and dismissal. For the speaker, negative stereotypical association produces a credibility deficit, with the hearer viewing a speaker sceptically because of their supposed lack of credibility. The logic is circular: the speaker lacks credibility because they belong to an untrustworthy social group.

Fricker regards credibility deficit as not merely an error in judgement but a form of epistemic violence. To her, the hearer’s judgement is epistemically flawed insofar as they dismiss a person’s testimony not because the evidence is lacking but because ingrained biases taint the speaker’s social identity. Fricker also regards the judgement as ethically flawed. Motivated by bigotry, the hearer affords validity to affective biases, presenting hate as a form of reason (we might call this Dawkins’ Fallacy). In the end, testimonial injustice dehumanises the speaker, denying not just their credibility but also the knowledge they possess and the experiences they enjoyed. By preemptively devaluing their testimony, the hearer deprives the speaker of basic respect while also stripping the legal system of basic justice.

Responding to Fricker, Emmalon Davis introduced the idea of credibility excess. Just as negative prejudices delegitimise and thus dehumanise, so too do positive prejudices distort perceptions of credibility. In this light, even well-intentioned judgements appear misguided, elevating a speaker not for what they say but for the positive stereotypes associated with their group. As Davis argues, speakers so blessed are often given opportunities they might not deserve, producing another layer of misrepresentation for the affected group. Moreover, and perhaps counter-intuitively, benevolent prejudices are a double-edged sword. By playing to the expected narrative, a speaker can boost their credibility; conversely, any deviation can lead to their dismissal. Think of Jonathan Glazer and the speed at which reverence turned to revulsion. Just like credibility deficit, credibility excess is a dehumanising trend, treating the speaker as fungible, a mannequin to be swapped with other members of their community as the need arises.

Fricker and Davis argue that these prejudicial considerations pervade everyday interactions, affecting who is believed and who is not. For example, this dynamic is common in lecture theatres. I suspect many readers have experienced classroom dynamics where the interventions of students from marginalised communities are dismissed as emotional while their dominant counterparts are celebrated as reasonable (or objective!), regardless of the actual content or merit of their respective contributions. Such dynamics illustrate how biases can elevate or diminish the value we assign to testimony, reinforcing prejudicial cycles of discrimination and injustice.

Having explained the influence biases wield over the credibility assigned to speakers, I now examine how anti-Palestinian racism produces contrasting perceptions of Palestinian and Israeli speakers. This case exemplifies the impact of credibility deficit and excess in geopolitical matters and the death and destruction that follow in their wake.

Racial Gaslighting: Normalising Catastrophic Violence

In the Euro-American bubble, the narrative surrounding Palestinians and Israelis often falls victim to a troubling dichotomy whereby liars are positioned opposite truth tellers (terrorists and victims is also a familiar trope). Entrenched across the bubble’s political, journalistic, and legal communities, this portrayal exemplifies high degrees of testimonial and epistemic injustice.

The attribution of credibility seldom stems from a balanced assessment of testimony, rather, bias comes to dominate perception. For example, the Orientalist caricature of the shifty Arab proliferates even today, not because it ever reflected any truth, but because the West sees Palestinians through a prejudicial lens (Arabs and Muslims too), painting entire populations with a broad brush of distrust. This cynical outlook is spread by the Associated Press, The Guardian, and the New York Times, who reference the “Hamas-run” or “Hamas-controlled” Ministry of Health; by Joe Biden who has “no notion that the Palestinians are telling the truth about how many people are killed”; and by Israel’s legal team which declared “that over a thousand of UNRWA’s employees have direct links to Hamas or other terrorist groups in Gaza.” Despite an abundance of evidence to challenge each of these claims, the assertions gain traction, neutralising Palestinian testimonies and Palestinian suffering along the way. Abu-Laban and Bakan frame these moves as racial gaslighting, a practice that is consistent with the anti-Palestinian racism common in the West.

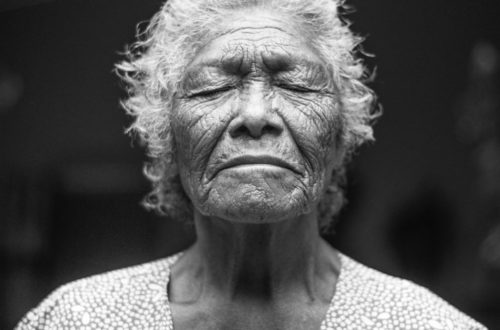

To Abu-Laban and Bakan, anti-Palestinian racism unfolds at three levels: the denial of the (neverending) Nakba, the mischaracterisation of Israeli apartheid as Jewish democracy, and a pervasive pattern of victim-blaming and scapegoating. Israel and its allies deploy each trope to “manipulate the discursive terrain of resistance,” pathologising Palestinian behaviour and testimony in the process. Whether it is biased terminology or high-profile political dismissals, the act of casting doubt on Palestinian accounts collectively disenfranchises the population. Palestinians must now contend with a discursive environment where listeners preemptively discredit their testimonies, declaring their experiences unworthy of belief (or grief). Alongside the spread of misinformation and disinformation, this pattern of epistemic violence entrenches Palestinian suffering. Israel’s obliteration of institutions like the al-Shifa hospital, the assassination of healthcare workers (provoking a “medical apocalypse” according to one publication), and the starving of children are rendered as contested events, open to interpretation, rather than horrific war crimes that demand accountability. Abu-Laban and Bakan conclude that “the powerful discourse of blaming the victim” leads to repeat situations where “reality is upended in a fog of racial gaslighting.”

Conversely, Israelis are portrayed as unerringly honest and morally upright, even when the evidence suggests the diametric opposite. For instance, just as Dr Tanya Haj-Hassan was detailing the assassination of her colleagues by Israeli soldiers in the al-Shifa hospital, Sky News questioned her about Hamas’ whereabouts. Statistics from Médecins Sans Frontières, the World Health Organisation, and the International Committee of the Red Cross are treated as meaningless, not because of doubts about the methodology or the veracity of the figures, but because they contradict the Israeli army’s pledge to only target terrorists. Likewise, despite being recognised as a liar by his former boss, Biden certifies that Netanyahu had provided “credible and reliable” assurances of compliance with international humanitarian law, including the facilitation of the delivery of aid. To Biden, Israeli assurances of legal compliance can co-exist alongside American airdrops and sea corridors; the blockade is “probably” famine-inducing but still IHL-compliant.

The concurrent amplification of false Israeli narratives—forty beheaded babies—alongside the discarding of genuine Palestinian ones—thousands of starving children—underlines the testimonial injustice we face. It is not just a case of reckless misrepresentations but of deliberate denials designed to influence policy and shape relations, dictating the course of political discourse and action. Testimonial injustice not only distorts perceptions of the Israeli occupation, but also perpetuates a cycle of anti-Palestinian racism, normalising the dynamics that allow for the catastrophic violence Israel is committing.

Ultimately, this pattern also corrupts the underlying epistemology of international law. Above all, proponents of the international legal regime claim that, however flawed, it remains an efficacious framework for the resolution of conflict. Yet, when assessed alongside the atrocities inflicted on the Palestinians, we are forced to conclude that international law appears sanguine about their annihilation, posturing as the solution while failing to restrain the actions of a tiny state that declares itself beyond the regime’s reach. What value does international law hold if it cannot prevent one state’s massacre of nearly 35,000 people, its maiming of over 100,000 (mostly) children, its starvation of 2,000,000, its absolute obliteration of every hospital and university in the region, and its ongoing encagement of a population? Where is the accountability for the soldier who declares that “a terrorist is anyone [we] killed in the areas in which [we] operate” or the government minister who boasts about being “proud of the ruins of Gaza”? For how long must we cling to the promise of international law? Has the real epistemic injustice been hiding in plain sight the whole time?

Troubling the Truth of the World

“Je ne crois pas un mot qui sort de votre bouche. Toute votre politique consiste à provoquer les Palestiniens.”*

Jacques Chirac speaking to Netanyahu

Given the systemic and dynamic character of anti-Palestinian racism, it is unclear what steps we can take to redress the testimonial injustice I have described. The Palestinian population in Gaza has been under occupation and siege for generations, with much of the population not knowing life outside of a concentration camp. In response to their plight, Euro-America now offers a stark choice between perpetual subservience and immediate destruction. In terms of political support, my favoured Third World does not fare much better. Beyond a handful of states—South Africa, Malaysia, Qatar, and Yemen—the remainder offer sympathy but little solidarity, reluctant to confront America’s darling. Perhaps we should not be surprised since many critical scholars have proven disappointing as well, behaving as if the scholarship we struggled to get on the books was symbolic rather than material, careerist rather than principled. What to do indeed?

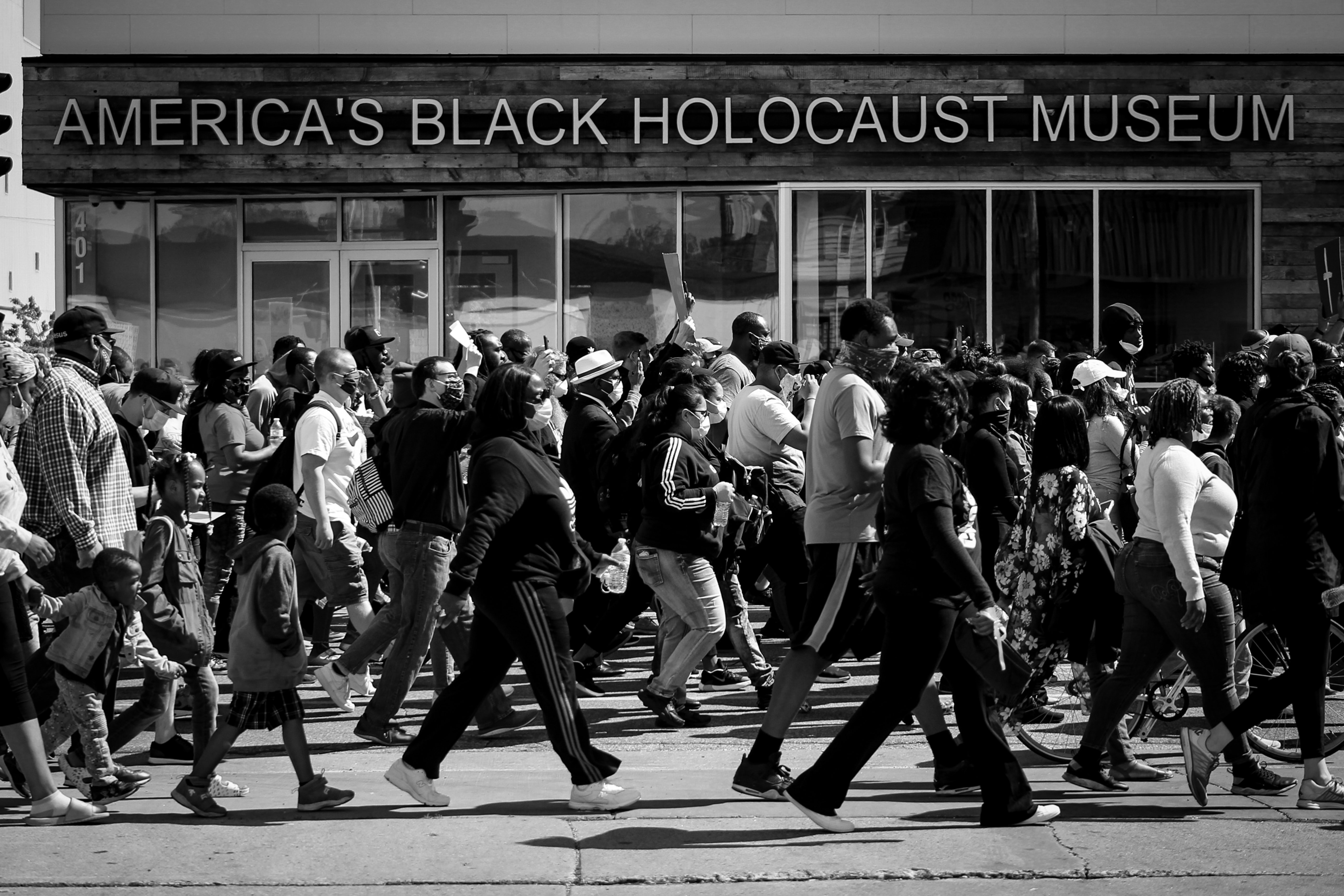

Fricker and Davis urge us to “trouble the truth of the world” as understood by the dominant subject. This means using a “reflexive critical awareness” to cultivate the “epistemic environment” in which we find ourselves, making it more inclusive of Palestinian voices and on their terms. The onus is not on Palestinians—nor on any marginalised group—to make themselves palatable to the dominant subjects. They need not disavow Hamas nor reaffirm Israel nor abandon resistance before we afford them the right of being heard. Such preconditions reinforce the very violence reflective critical awareness is meant to counter.

Rather, it is for us to acknowledge that the epistemic injustice we have normalised has created conditions for the savagery Israel perpetrates today. “Dominant hearers must recognise that epistemic environments in which marginalised individuals can speak are notably few and dispersed and may constitute substandard spaces for these individuals to be heard.” The epistemic environment cultivated by international law has long been a hostile space and, judging by the ICC prosecutor’s tolerance for a mushrooming catalogue of war crimes, at least when Russia is not involved, it will remain so.

In light of these reflections, the path forward might be clearer than I first realised: to challenge the credibility gap assigned to Palestinian and Israeli narratives we must take direct action that rejects the stratification imposed upon us. More than an academic exercise, we have a moral obligation to elevate Palestinian narratives, not moderated by unjust structures, but as they are lived by Palestinians. Here, I tip my hat to Francesca Albanese, Michael Fakhri, and Balakrishnan Rajagopal for their brave and unflinching moral leadership. These three UN Special Rapporteurs have continued to document the suffering of Palestinians as well as Israel’s breaches of international law. They do so at great personal risk, with special note to Albanese who is routinely threatened in the most vile ways by allies of Israel (including the US State Department which either recklessly or deliberately smeared her this past week). Their recommendations bear repeating here:

- An arms embargo and economic sanctions levelled against Israel;

- Support for South Africa’s resort to the UNSC under art 94(2) of the UN Charter;

- Lobbying Karim Khan to pursue arrest warrants for Israeli officials responsible for a litany of war crimes as well as domestic prosecutions of dual-citizens who return to home countries after fighting for the Israeli army (South Africa and France have already committed to such action and efforts are underway in the Netherlands and the UK);

- The deployment of an international presence in the Occupied Palestinian Territories to protect Palestinians against the violence of the Israeli military and settler militias; and

- The expulsion of Israel from the United Nations until it ends its occupation of Palestine and dismantles its apartheid regime.

Each of these steps is viable and there is already momentum behind them. For academics, an array of micro-actions is also available: platforming Palestinian colleagues, publishing their works, and centring their pain. Above all, the BDS Movement remains an effective form of activism, designed to isolate Israel from the rest of the world in much the same way as Israel has attempted against the Palestinians with its illegal apartheid wall. In the past few months, several student unions have mobilised, insisting their universities divest from companies that support Israel while highlighting the Israeli academy’s complicity in the violence of apartheid and occupation. The importance of this movement explains why Israel has lobbied the UK and other states to criminalise BDS, reminding us of King’s cogent observation: those who make peaceful revolution impossible, make violent revolution inevitable. The time for symbolic gestures has passed; our actions must now be tangible, principled, and unyielding.

Perhaps this is the reflexive critical awareness Fricker and Davis advocated for: to stand in solidarity with the Palestinian people involves taking definitive steps towards dismantling the broader structures of epistemic injustice. By doing so, we confront the foundations of our understanding and engagement with the world. Only through a concerted collaborative effort can we hope to free international law of the anti-Palestinian racism and epistemic injustice we have treated as normal for far too long. In the end, we may even save its credibility.

*I don’t believe a word that comes out of your mouth. Your entire politics consists of provoking the Palestinians.