Only Paradoxes to Offer: The Malleable Nature of Human Rights

I was recently challenged about my latest post on democratic capitalism. To introduce the topic, I alluded to unwavering political / popular support for human rights. My comment was off-the-cuff and, as a reader rightly pointed out, inaccurate. Theresa May and Boris Johnson, UK prime minister and foreign secretary respectively, have spoken out against the European Convention of Human Rights and the Human Rights Act. Nor was David Cameron much better, refusing to implement rights-based decisions of the European Court of Justice. Another former British prime minister, Tony Blair, treated human rights protections like playdough. When considered through a governmental lens, my off-the-cuff remark was not only inaccurate but just plain wrong. And I stand corrected. But there is more to this post than a retraction.

How do we conceive of human rights? Admittedly, the question is difficult to answer and I teach an entire course – Theories of Human Rights – on this very topic. To the layperson, the human rights regime represents a closed edifice: its protections are neatly packaged in an enclosed structure. When necessary, a claimant enters the structure and draws upon the protections, much like a bank. Except that it is not this simple.

At their core, human rights exist to i) protect individuals by restraining state agents and ii) to promote human dignity by establishing an array of entitlements. Subjectivity in our identities and experiences translates into a mix of perspectives on what human dignity looks like and, therefore, which aspects should be formalised, either as safeguards or services (more on the bipartite character of human rights in a forthcoming post).

To account for human diversity, human rights treaties / acts are drafted in aspirational tone often drawing upon abstract terms, two techniques that are deployed to facilitate flexibility in application. This leads us to our first paradox: flexible language is needed for flexible application but flexible language also creates flexible obligations, carving rhetorical escape routes for rights violators. It is no longer a matter of entering the structure and drawing upon protections but of convincing the gatekeepers to let you in. Indeed, instead of the simple application of protections, we are left with complex manoeuvres in interpretation and persuasion. To the orator go the spoils…

To counter the escape routes without suffocating diversity in dignity, we subject human rights to the endless normativity treatment, designing protections around a cornucopia of characteristics. Some rights protections are afforded according to demographics – women, children, and even prisoners – social aspiration – equality, literacy, and fair wages – and jurisdiction – the Human Rights Act (municipal), the European Convention of Human Rights (supranational), and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (international). With a little effort, we uncover even more categories. Some rights merit absolute protection – right to be free from torture – qualified protection – right to life (surprising to many but the death penalty is not a violation) – or progressive realisation – right to tertiary education. Some rights demand positive action by the state – right to water – while others impose a negative obligation not to interfere – right to free speech.

Subdivisions are many and layered. Nevertheless, there are certain characteristics that transcend type: in all instances, rights apply universally to the protected group; they manifest at the individual level; and they are mediated by the state. In practical terms, this means that any woman could ostensibly bring a claim against a government entity for violating a statutory guarantee of equal pay. Notably, it also means that the woman-claimant must demonstrate personal injury at the hands of a state agent along with availability of a viable remedy if her claim is to be successful. Without remediable injury or a liable agent, her claim fails.

That she can bring a claim for a violation of equal pay obligations is worth celebrating. Human rights represent a praxis of emancipatory politics. By creating guidelines for state behaviour, we establish standards of state accountability, allowing individuals to name and seek redress for human violations, making human suffering both visible and actionable. Enter our second paradox. Language is both inclusive and exclusive, subject to the politics of definition. By creating violations, we simultaneously constitute non-violations, behaviours that the state will not be held to account for. Yet the division is not nearly as objective as the legal protections imply. For example, the death penalty is not a violation of the right to life. Why not? Solely because it has been constituted as a non-violation and nothing else. A political decision is now a legal reality with implications for the acts a state can carry out such as legitimately killing people.

State authority leads us directly into the heart of our third paradox. Human rights represent a legitimation of state power. Consider that human rights are adopted at the executive level – in the form of a treaty – or at the legislative level – in the form of an act. In both instances, the state is identifying a series of protections that it agrees to be held accountable for. What of the standards it does not wish to be held accountable for? The answer is self-evident: they are not constituted as human rights protections and thus exist as nothing more than thin air. For example, is torture in the UK prohibited? Sort of. In a detailed investigation by Ian Cobain, we are provided with ample evidence that both MI5 and MI6 have created conditions to allow its intelligence agents to obtain information through torture without dirtying their hands or, more importantly, triggering the state’s liability. In the agencies’ own instructions to its agents, much is said about protecting human rights but much more is said about which activities occupy a grey zone and are thus insulated against human rights claims.

In short, are human rights emancipatory? Certainly! Human rights provide us with an edifice, language, and institutions to hold states to account. Are human rights repressive? That too! Human rights constitute violations and non-violations equally, adumbrating standards of accountability but also escape routes for violators (who are deemed non-violators if they successfully escape). The state, with omnipotent authority, declares which standards we can hold it to account for: nothing less but, equally, nothing more.

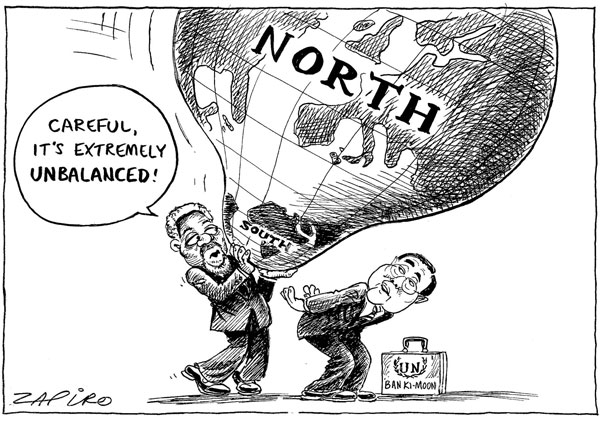

The nature of human rights therefore depends on the conception of human rights at play. May, Johnson, Cameron, and Blair regard human rights as a necessary evil: an inconvenience for their moral convictions but one that can be adroitly sidestepped and even leveraged in support of their political ambitions. May argues that withdrawing from the European Convention of Human Rights will allow for greater human security; Johnson tells us that colonialism – or the denial of human dignity – is good for ‘Africans’; Cameron believes that the European Court of Justice can be ignored because the thought of recognising prisoners’ rights ‘make him sick‘; and Blair, not to be outdone, justifies the large-scale massacre of hundreds of thousands of Afghans, Iraqis, and Palestinians in the name of world (or at least British) peace. Their conception of human rights is an instrumental one that begins and ends with national state interest. Nor are they alone in their paradoxical view of human rights protections with many laypeople now believing that the state should use torture to protect human rights.

Orwell is either laughing or weeping.

N.B. There is a fourth paradox – individual liberty as an expression of collective solidarity – but this is best discussed in the forthcoming post about the protection-promotion dichotomy I mention above. In the meantime, you will find a hint in the image above. Check back next week!